Heroically Misunderstanding Opera, Act I

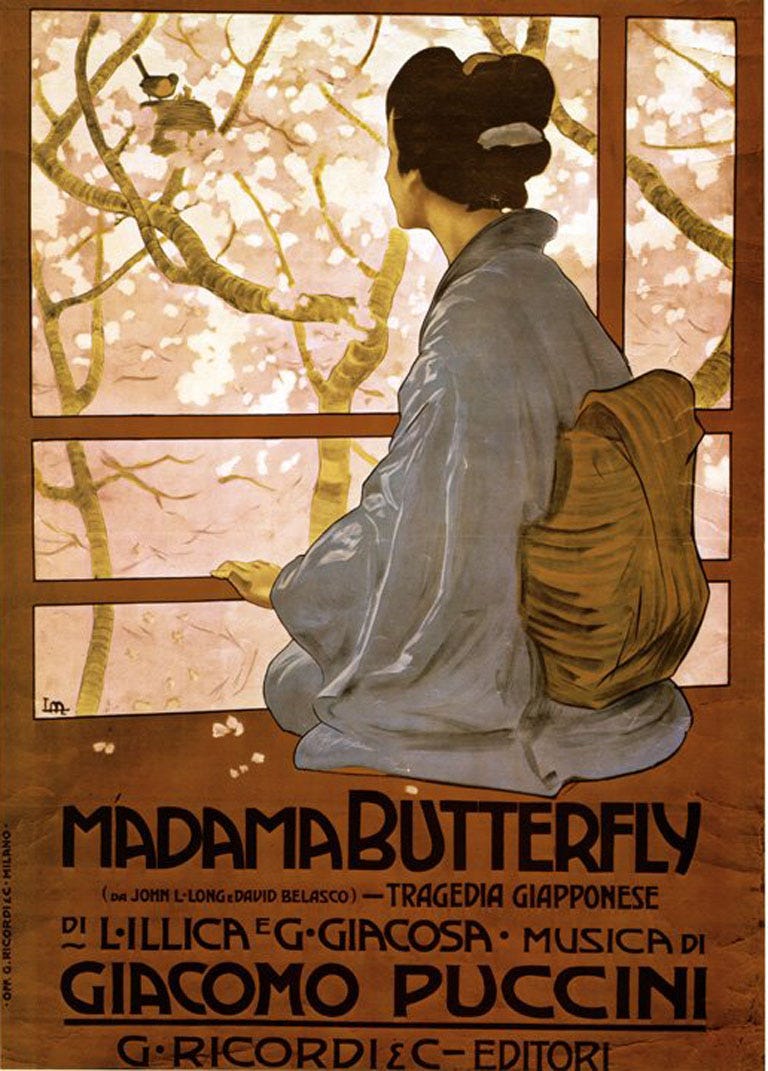

An editorial that recently appeared in the San Francisco Chronicle argued that a number of “orientalist” operas, such as Madama Butterfly, are “aggressively racist.”

Although the author, Ms. Kaneda, is a professor of music, and I am not, I was surprised to read in her piece arguments that reveal a rather embarrassing misapprehension of how opera works.

The main points of Ms. Kaneda's piece regard the plot of Puccini's opera Madama Butterfly. Readers unfamiliar with the story can find it elsewhere. However, in her critique, she refuses entirely to acknowledge the simple point Puccini is making, dramatically and musically. (I say “refuses” because it is disqualifying of a professorship in music for the scholar not to have noticed these.)

Cio-Cio-San (Madama Butterfly) is undoubtedly the strongest character in the opera. Although abandoned by her husband, Pinkerton, she is the primary mover of the drama and the one with whom the audience's empathy lies for the entire duration of the runtime. We already distrust her philandering fiancée within minutes of “meeting” him. By the final act, the audience has something even lower than contempt for Pinkerton. All of this is by Puccini's design.

To claim, as Ms. Kaneda does, that the opera “objectifies” Asian women is to purposefully misread the plot, the music, and every other dramatic indication available. Frankly, it's Ms. Kaneda's own problem if she “can’t help but associate [it] with violence and dehumanization.”

Cio-Cio-San's famous aria, “Un bel di vedremo,” is among the most memorable dramatic climaxes in opera. In her unflinching certainty that Pinkerton will one day return, she shows us what love means, and in moral standing eclipses every other character. The aria typically leaves no eye dry in the house.

Yet, Ms. Kaneda, deaf to emotion, claims, “That beloved aria’s moment of transcendence comes exactly when Cio-Cio-San stops singing. Silence is the condition of her humanity. The orchestra finishes the number without her.” It is hard to hoist victimhood onto a character that belies the label, isn't it?

In her cursory study of misogyny and orientalism, Ms. Kaneda conveniently fails to mention the most impressive Asian female in opera: Turandot is the story of a Chinese princess feared and obeyed by all. That opera’s resolution celebrates the triumph of love and freedom over tyranny. Uncharacteristically for the genre, both Turandot and her lover are still alive at the end. Which brings me to another point...

Most dramatic operas are tragedies, which, by definition, require the death of the principle, usually titular, character. To whine that “the “Oriental” woman’s role in opera is to die” is to heroically misunderstand the subject matter. Death, it bears mentioning, doesn't discriminate. Tristan and Isolde don't make it to the end. Neither do Tosca and Cavaradossi, Aida and Radamès, or Don Giovanni.

Finally, I am puzzled by the claim that supposedly orientalist “works like “Aida,” “Madama Butterfly” and “Carmen.” ... [feature] lurid treatments of sex, violence and opulence that would have been considered offensive if they depicted European women in a European setting.” Again, I suspect Ms. Kaneda’s credentials.

First, it is bizarre to criticize Aida of wanton orientalism, as it was commissioned by the Khedive of Egypt to commemorate the opening of a new opera house in Cairo, where it premiered.

Second, the “violence” and “opulence” in these operas is no where close to unique. It is a true stereotype of 19th century opera that most of them feature duels, blood feuds, or war, and almost all of them are over-the-top.

Remember that these were all written at a time when there were no blockbuster movies - these characters were the superheros, and they had to be entertaining. Those with less contempt for special effects get to enjoy in Aida one of the greatest opportunities an opera house has to show what they can do.

Second, Carmen takes place in Seville, which, last I checked, is a part of Europe. While Carmen is a gypsy, this point is brought up to emphasize her social status relative to other characters. Her ethnicity plays no role whatsoever in the story.

Carmen’s sexuality is indeed a dramatic wedge in the plot of her opera, just like with innumerable other male and female characters, such as Violetta in La Traviata (France), Maddalena in Rigoletto (Italy), Isolde (England), Don Giovanni (Spain), and Manon Lescaut (France), to name just a few. So much for the suggestion that overt treatments of sex wouldn't fly in “European operas.”

There exist apt criticisms of Orientalism. Ms. Kaneda's piece does not rank among them. It is a lazy editorial peg to relate a story of unrequited love in 19th century Japan - that can be read, incidentally, as an indictment of American imperialism - to the Atlanta shooting.

While it's popular now to coarsely graft critical race grievances onto any subject, that doesn't mean it sticks. The real act of racism is to be so myopically fixated on immaterial differences, such as ethnicity, that one becomes blind to the universal experience a fictional character represents.

Want to share your thoughts on this essay? Leave a comment below.

Subscribe to the newsletter to receive new essays directly in your inbox.