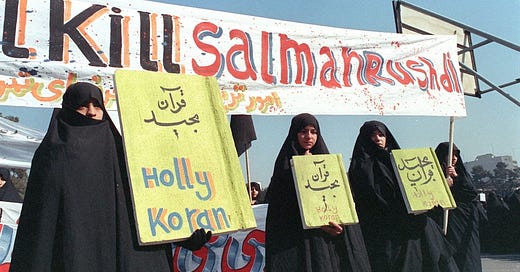

The Islamists' greatest weapon

The West has lost its desire to defend its most important values. The fundamentalists have not.

For thirty-three years, Salman Rushdie had avoided attack despite numerous attempts to carry out the fatwa. Since 2001, the author has lived freely in New York City, while the bounty jackpot gradually ticked upwards in fits and starts. But the bounty was always a red herring. “If you were thinking of collecting,” Rushdie once quipped, “I think it would be quite difficult. The fact is that the danger to my life was never from [some number]. The danger to my life was from professional assassins being dispatched from the Iranian state.”

So when the Iranian regime formally “disavowed” the fatwa in 1998, Rushdie began the slow climb out of hiding. But while Rushdie eagerly embraced his return to normalcy, courageously refusing to let the edict cast a forever shadow onto his life, the truth is that the threat never really disappeared.

The question that remains is: why now? Of all the occasions in which the author sat unguarded before an audience of hundreds, why only now did someone storm the stage, knife in hand? In the bucolic setting of the Chautauqua Institution no less, a destination much more tedious to get to than any venue in New York City or London where the author had spoken countless times in the last two decades.

Two forces are at work here. First: Islamic fundamentalism is not in decline, and its influence finds little resistance in the West. Second: Few voices are still willing to defend, without equivocation, the culture of free speech, and the enemies of free expression have taken notice.

The assailant who carried out the most successful attempt to realize the fatwa was no aging former agent of the Iranian regime, but a 24-year old born and raised in New Jersey. Hadi Matar was allegedly radicalized following a 2018 trip to a pro-Hezbollah region of Lebanon. He idolized the Ayatollah Khomeini and had contact over social media with members of Iran’s Revolutionary Guard. Following the attack, hardliner newspapers in Iran celebrated the “brave and dutiful person who attacked the apostate and evil Salman Rushdie”.

Meanwhile, bolstered by the readiness of left-wing activists to smear any critique of Islam as “islamophobia”, a soft censure has come to settle on Western media, which has welcomed de facto blasphemy laws.

Thus, when PEN America honored the massacred cartoonists of Charlie Hebdo with the Freedom of Expression Courage award, hundreds of PEN members objected in a beggarly letter that couched anti-blasphemy sentiments in the language of intersectionality:

“Power and prestige are elements that must be recognized in considering almost any form of discourse, including satire. The inequities between the person holding the pen and the subject fixed on paper by that pen cannot, and must not, be ignored.”

One inequity not mentioned by the signatories is that between the living (the offended camp) and the dead (the satirists who treated all ideologies with equal scorn).

Increasingly, Western values appear only in quotation marks when in print, and are necessarily pronounced with derision in conversation. Today in the most “tolerant”, free and privileged cities, expressing dissent - or even insufficient agreement - on a wide and nebulous cluster of topics from race and income inequality to the biological basis of gender and sex can result in disastrous social and professional consequences. But these new rules and orthodoxies do not plague Iranian society nor any other society outside the West.

As Bari Weiss writes,

“Of course it’s now, when we’re surrounded by silliness and weakness and self-obsession, that a man gets on stage and plunges a knife into Rushdie… Of course it is now, when words are literally violence and J.K. Rowling literally puts trans lives in danger and even talking about anything that might offend anyone means you are literally arguing I shouldn’t exist.”

In Iran, courageous women continue to fight a long battle for the simple right to leave their homes without the veil or the genuine threat of police brutality. The activist Masih Alinejad continues to fight for fundamental rights for women, despite being the target of multiple foiled assasination attempts, allegedly orchestrated by the Iranian intelligence network, on American soil. These are the movements that urgently need our support. The “words are violence” camp urgently needs our ridicule.

In the aftermath of the attack, we are faced with a test even more important and even more clear than that presented in 1989. There is only one response to the attack: the unequivocal condemnation of violence against an author of fiction, and unbridled scorn for the censors and their pink-haired apologists.